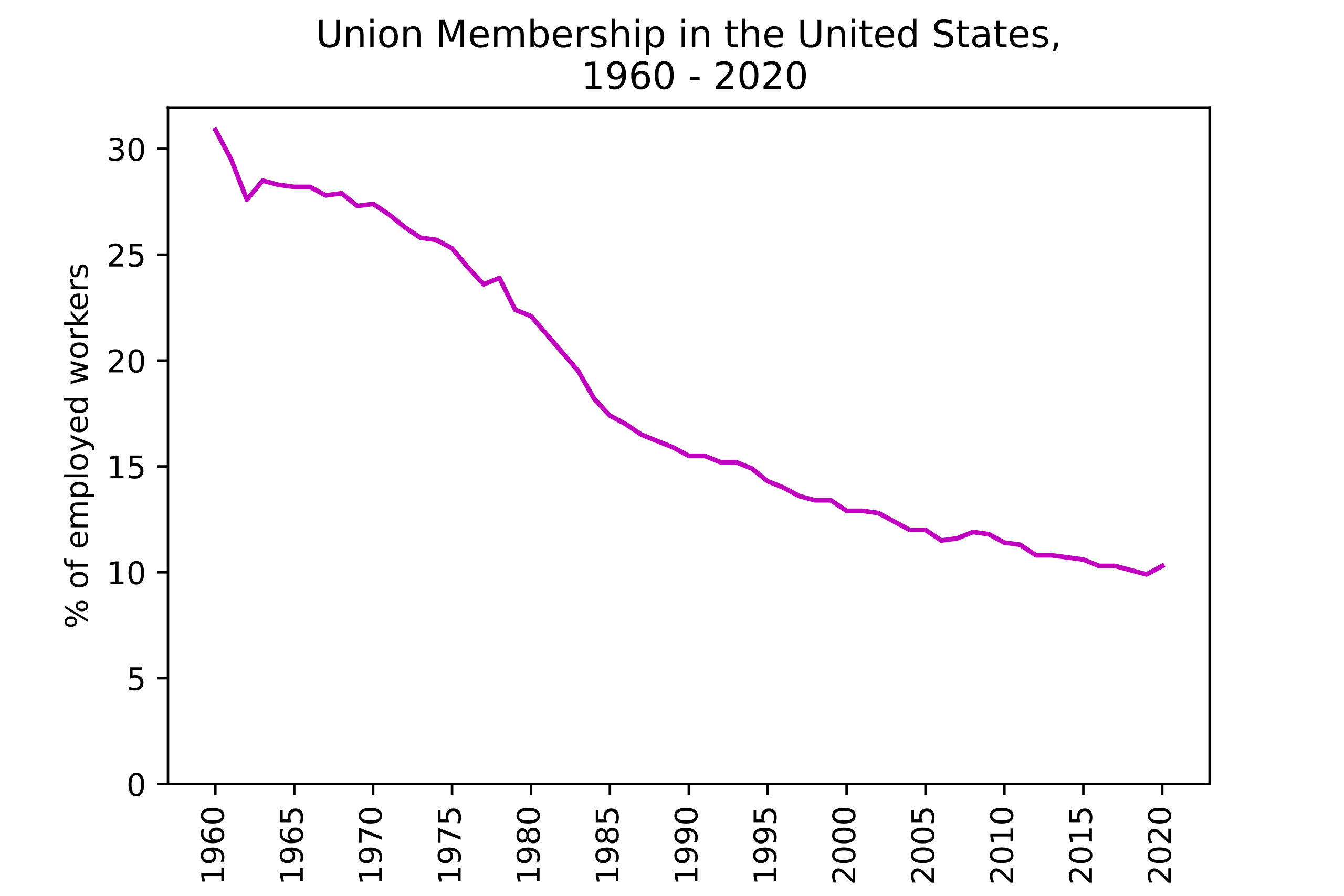

Let's look at another graph! This one shows union membership and income inequality in the US plotted together.

While correlation doesn't equal causation, this plot definitely sends a message. Before I get to the first question I raised, I'm going to talk about the second: who is a union for? Watching the 2023 Christopher Nolan film Oppenheimer last weekend, I took notice of a scene where Ernest Lawrence, a physicist at the University of California-Berkeley, indignantly responds to a group of researchers proposal to unionize by asking them what they have in common with dockworkers or day-laborers, insinuating that they have less reason to unionize than manual labor, working class employees. This is still a canard that finds its way into union discourse in our current era, now mostly being directed at Starbucks baristas, teachers, and graduate students in their attempts to unionize throughout North America. The message is clear: if you don't fit the conservative/Republican stereotype of a worker, which is mostly limited to anyone wearing a hardhat, coal miners, and folks transporting panes of glass across busy city streets during car chases, then you're not a "real worker" working a "real job." Of course, this is pure drivel, animated mostly by a sense of cultural grievance towards professions that the figure in question happens to dislike, which unsurprisingly tend to be professions dominated by young people and women. But I'm going off on a tangent here. The question that really matters, much more so than the issue of who a "real worker" is, depends on your beliefs towards employer-employee relations as they relate to wages: if you think that the best system is employers offering potential employees a take-it-or-leave-it contract, with no room or position for the employee to negotiate wages or benefits, then you're going to be opposed to unionization. If you think that the best system is employees being able to negotiate wages or benefits with their employer via collective bargaining, then you're going to be amenable to unionization. So that's ultimately the only answer to who a union is for: it's for workers who feel the best system is one in which they can negotiate their wages and benefits with their employer.

Back to my first question: what does a union do? At its core, a union provides a vehicle for negotiation between an employer and employee, as I talked about in the last paragraph. The main means to do this is through collective bargaining, or negotiating the terms of employment with your employer. In the case of any member of PSAC 610, this is the University of Western Ontario. This year is a particularly important one for PSAC 610 members, as it is a bargaining year. Why would we need to bargain? Well, just look at the headlines.

The results are in: the cost of living is going up, and it's getting harder to get by, especially on graduate student wages. To add insult to injury, what we make here at Western as teaching assistants is far below the Ontario minimum wage (which will be $16.55 an hour, starting October 1st, 2023), considering we all work well past the 10 hours a week specified in our TA contract. PSAC 610's contract with Western expires August 31st of this year, which means that afterwards we will formally begin the bargaining process. If you're a Western student reading this, over the past couple months you should've gotten an email for a survey about issues you've had as a TA, or an email about a departmental town hall where you could voice your concerns in-person. If you didn't get a chance to do either, you can email me or talk to me in-person! I'm optimistic for this year's bargaining, as postdoc bargaining earlier this year resulted in a roughly 8% wage increase, and the unconstitutional ruling of Ontario's Bill 124 means that the 1% wage increase cap on public sector employee wages is not in effect like it was during the last bargaining year for PSAC 610. So there is grounds to feel good about tangible betterments to graduate student finances. We'll see what the future holds!