September 7th, 2022

Introduction, or, what I did on my summer fieldworkcation

Hello all! I'm Reid, now a second year PhD student working with Dr. Catherine Neish at Western University (or the University of Western Ontario). For this blog post, I'm going to talk a bit about what my path's been up to this point.

I first got interested in the surfaces of rocky and icy planetary bodies late in high school, and majored in geology during my undergraduate education for this reason. I was fortunate to work as an intern at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory for a year after graduating from undergrad, and went on to earn a master's degree in Wesleyan University's planetary science program. After this, I spent a couple years working jobs mostly unrelated to science or academia before entering Western University as a PhD student. Before coming to Western, much of my research had to do with interpreting radar data of planetary bodies such as the Moon and Venus. At APL, I mapped out permanently-shadowed regions on the lunar poles and looked at their corresponding radar values in Mini-RF circular polarization ratio (CPR) data. My master's thesis involved using reprocessed Magellan radar data to survey the rough tessera terrains for possible impact craters, as well as a study of material infilling dark-floored craters on the surface of Venus.

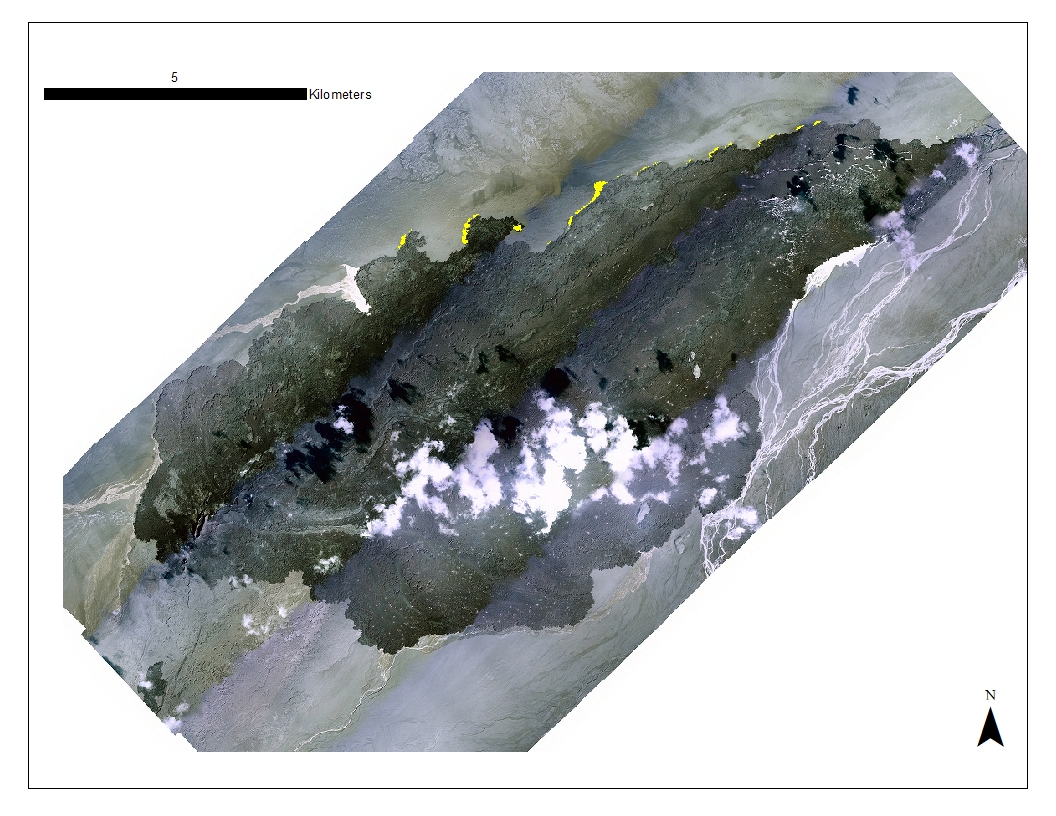

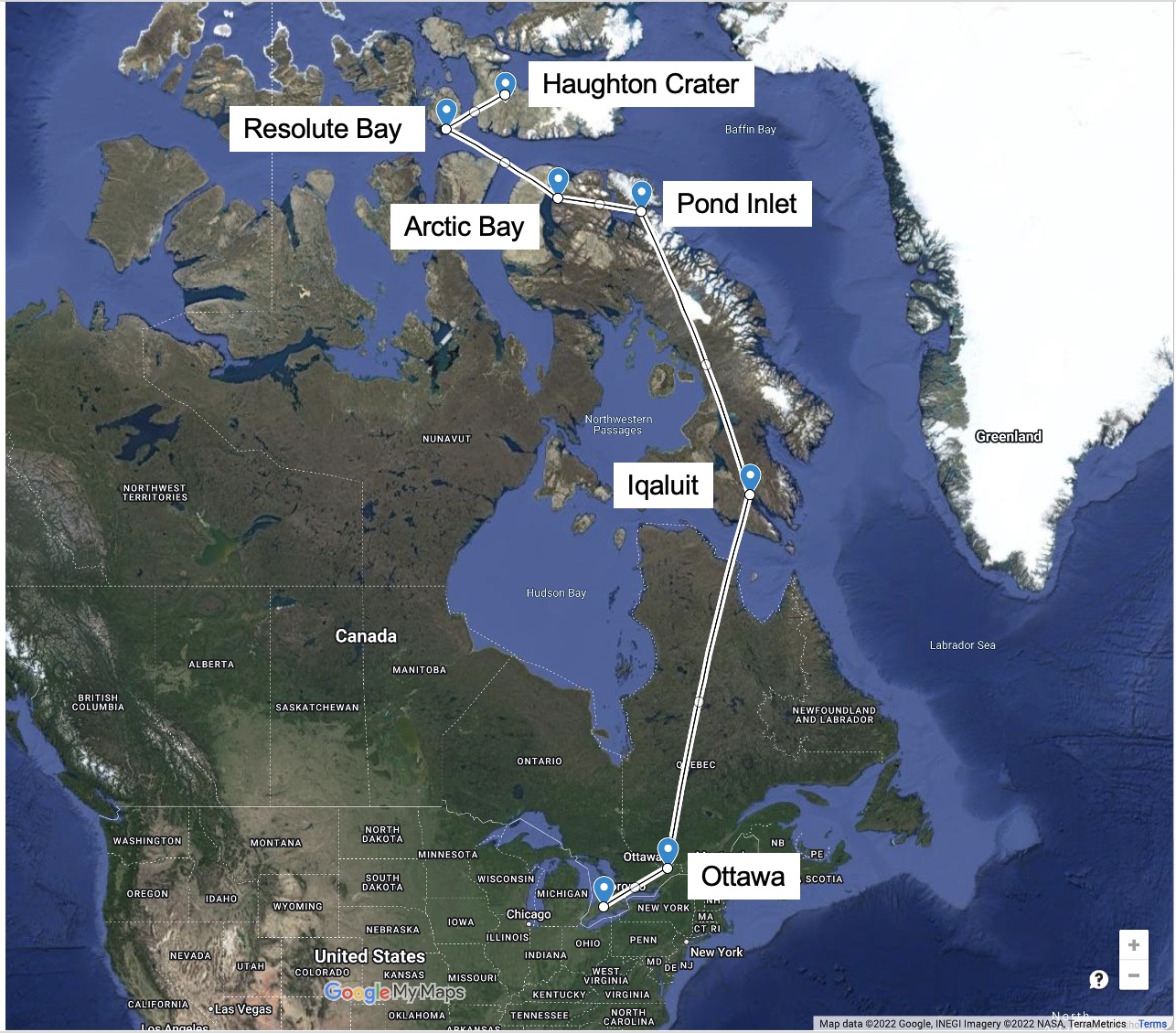

What do I do here at Western? Well, I get to continue to try to understand how radar works. I'm not fully there, but I'm starting to. That's why I'm here, after all. My past radar work was mostly concerned with properties associated with impact craters, as a kind of record of past events like volcanism or deformation. At Western, I'm using radar datasets to understand processes that may be currently occurring on planetary bodies ranging from Earth to Mars-- specifically, aeolian processes, or the mantling of wind-driven sediment on planetary surfaces. How does sediment that's covering the surface of a rough lava flow affect the radar backscatter? Using the Holuhraun lava flow in Iceland as a study area, I'm trying to understand the question and the implications it may have for our understanding of lava flows on Mars. To begin to answer this, I've looked at several dozen radar observations of the Holuhraun lava flow-field from 2015 to 2021 to see how the lava surface has changed over time as reflected by the radar backscatter values. What I've found so far is this: although we don't see much a change in the large scale, along the margins of the lava flow there are distinct regions that are extremely radar dark when looking at recent radar imagery and are also distinctly mantled by sediment when examining them in aerial imagery. What's nice about Holuhraun is that, unlike Mars or Venus, in addition to examining remote sensing datasets, we can also study sites in-person!