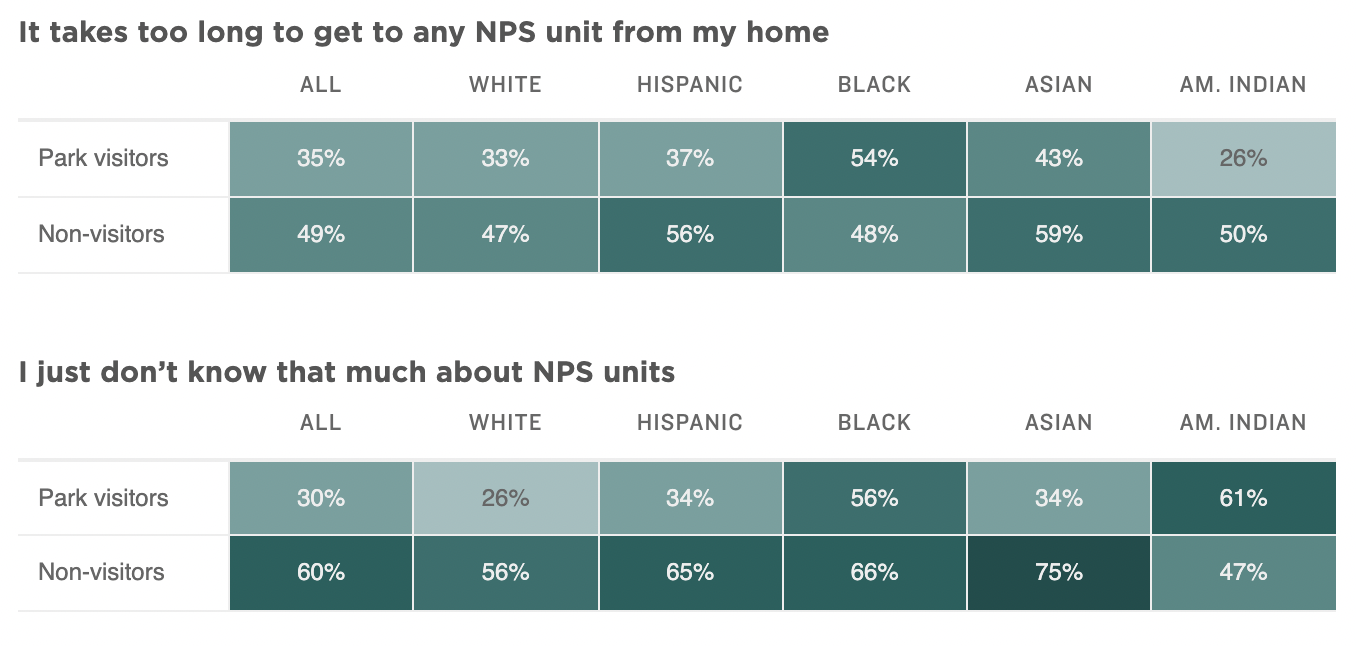

A recent article by Dawson (2018) published in the journal Public Understanding of Science examined this point in great detail. Just who is included, and feels included, in science communication and science outreach? The author interviewed individuals from several immigrant, ethnic minority communities in the UK, finding a common refrain: while there was a stated purpose by institutions such as science museums and science centers that felt their work was for the public benefit and served as a vital tool to include members of the larger public in science communication efforts, many Londoners who came from certain backgrounds felt differently. As one interviewee--a member of the Somali community named Fatima--put it, going to museums just reminded them of being forced to go to museums as a school group. Participants in the study noted that institutions such as museums had the reputation of being "high-brow" and coming off as inaccessible and unwelcoming to their communities. An NPR article on the efforts to increase diversity amongst US national park staff and visitors further underscores this point. Luis Perales, chief academic officer at Changemaker High School, is quoted as saying that "spaces are either inviting or are rejecting in many ways. And I think that what's been created [with national parks] is the idea that this is not your space." In a 2008-2009 survey put out by the park service, there was a strong sense among certain communities, especially minority groups, that national parks were either inaccessible physically or that they didn't know much about national parks. Dawson (2018) discusses the results of the UK Public Attitudes to Science (PAS) report, which noted that of those surveyed who reported not feeling good about science, not trusting science and/or not participating in science communication activities, disproportionately represented were members of ethnic minority communities, socio-economically disadvantaged communities and women.

These two articles are only the tip of the iceberg, but what's clear is that there are many cases where science communication efforts have failed to equitably serve the entirety of the public, instead seeming to further entrench along lines of race and class. As a grad student, scientist, or a concerned member of your community reading this, you may be asking: What's going wrong? Why are science communication efforts failing to reach certain groups? To answer this, I think it's helpful to ask: what are the criteria for what constitutes science communication? Is this adequate? Or do we need to rethink what goes into effectively communicating science?

A study by Kappel & Holmen (2019) explored this area by examining what the stated goals of science communication are, as enumerated by a recent report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The report listed five goals of science communication, including: 1), sharing recent findings and excitement for science, 2), increasing public appreciation of science, 3), increasing knowledge and understanding of science, 4), influencing the opinions, policy preferences, and behaviors of people, and 5), ensuring that a diversity of opinions held by different groups are considered when solutions to social problems are pursued. Kappel & Holmen (2019) expressed criticism that these goals were generally too undetailed and underexplored to be of any great use, proposing that science communicators be mindful of whether their efforts are more dissemination (one-way communication) or participatory (two-way communication). On this note, I'd like to end by proposing a few questions. For those who have experience in science communication, did you get a sense that there was a disparity between its aims and the event/activity in practice? What accounted for this? Do you feel that your experiences were more one-way or two-way in communication style, as noted by Kappel & Holmen (2019)? For any planetary scientists reading this, what are some advantages and disadvantages planetary science has insofar as science communication? When it comes to engaging and reaching members of underrepresented groups, what are the strengths and weaknesses of the planetary science community insofar as its science communication efforts? Do you feel as if there are competing interests in planetary science communication (public awareness vs. policy consultation vs. student recruitment)?

That's a lot of questions so I'm going to end it here for this week. Until next time!

NPR article on NPS visitor demographics: https://www.npr.org/2016/03/09/463851006/dont-care-about-national-parks-the-park-service-needs-you-to

Dawson (2018): https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0963662517750072

Kappel & Holmen (2019): https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2019.00055/full