2. There's an impact structure. Also pretty cool. Unfortunately, that's about it. Points 3 through 10 of this list don't exist. Sorry.

Three weeks ago, myself and my intrepid group members (Daliah, Andrew, and Tara), were ankle-deep in bog water just south of the city of Sudbury, Ontario. We were getting a bit too bogged-down in the details. Now you're probably thinking *record scratch* just how we got ourselves in this situation?

The whole story starts about 1.85 billion years ago. It was a Tuesday. A bolide, or projectile streaked through space and had the good fortune to hit this very rock floating in our slice of the cosmos. What happened next may shock you! It certainly did that to quite a few of the rocks we saw.

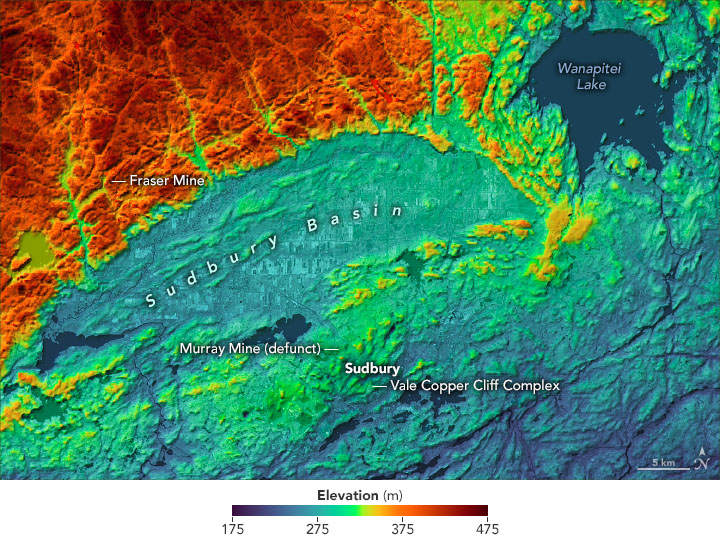

The resulting impact formed a crater that, having been significantly deformed in the years afterwards, resembles something quite unlike the textbook impact craters you find on the Moon or Meteor Crater in Arizona. Nowadays, it's typically referred to as the Sudbury Impact Structure. To the north and west of the impact structure, you have the rocks of the Archaean-age (meaning greater than 2.5 billion years old) Superior Geologic Province, and to the south, east, and west, you have the slightly more spry rocks of the Proterozoic-age Huronian Supergroup. So we have all these rocks around the crater. Aside from the general shape, which has become a bit unrecognizable as a crater in recent years, how can we tell that an impact happened here? Well, you walk around in the field and look at rocks. But not just ANY rocks. There are two main lines of (naked-eye) evidence in the rock record of an impact site like Sudbury for the past impact. The first and most dramatic are shatter cones!

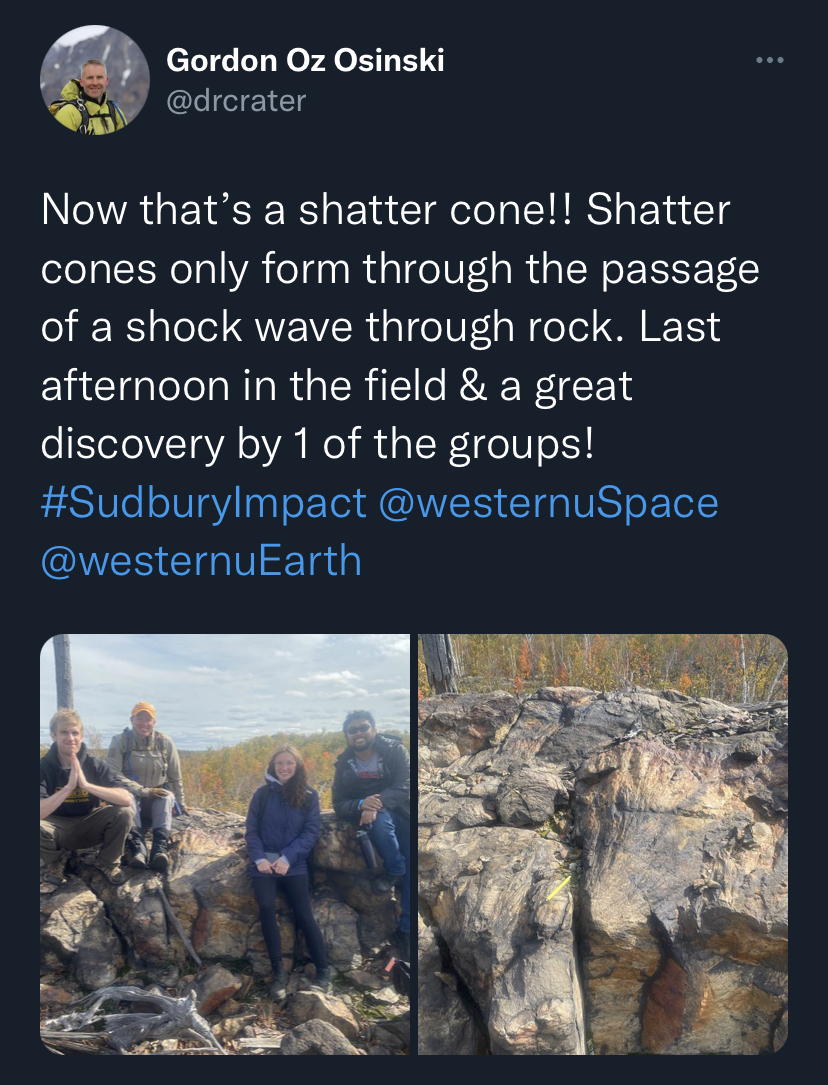

Shatter cones are actually used to describe less a specific rock type than the texture that results from rock being subject to the high pressure shock wave that you only get from a bolide impact. Or nuclear test. Nuclear weapons were not around 1.85 billion years ago, leaving us with the conclusion that the shatter cones we observed at Sudbury are indeed due to meteorite impact. Shatter cones have a distinctive, radial texture that almost looks like a seashell, one of the only naked eye indicators of an impact event. We found dozens of instances of shatter cones in the field at Sudbury, ranging from around a dozen centimeters to meters-wide shatter cones. In particular, our group happened upon an extremely large shatter cone on the last day of us being in the field.

Anyways, back to myself and my group members being stuck in the bog. This was the result of one of the small decisions a field group can make by which the outcome is not immediately known. As we were all newcomers to the Sudbury area, we had occasional moments of having to take time to get our bearings, check which direction the sun was in and what time it was, and decide on the fly as to what our priorities were as far as research. I haven't been involved with any geological field research since mid-2015-- about six-and-a-half years ago! While my last field experience involved several short exercises per day in order to understand the geology of central California, my group's work at Sudbury was focused much more on a single goal: finding field occurrences of Sudbury Breccia.

I mentioned that there were two main lines of (naked-eye) evidence for an impact in the rock record. At larger impact sites like Sudbury and Vredefort in South Africa, you also get examples of impact breccia. In general, breccia is a term for a rock composed of clasts of highly angular rock that are lithified together, which can have non-impact origins. As Oz pointed out on our first day in the field, many examples of Sudbury Breccia are somewhat deceiving-- the clasts are more rounded than a textbook example of breccia, perhaps more akin to a conglomerate. In the field, our group set off late in the morning on Wednesday, September 29th with dreams of well-exposed outcrops of Sudbury Breccia in our heads. Did we find any? At first, no! Then yes!

From the couple of outcrops we went to with Oz and the rest of the class in the first couple days of the week, we had a heuristic for identifying Sudbury Breccia in the field. Distinct, subrounded clasts at least one rock type within a matrix of the other. Seems pretty simple, right? WRONG. It is for this reason that Sudbury, Ontario's past industrial activity became the bane of our existence. As you make your way around the greater Sudbury area, stopping at outcrops along the way, you may notice that quite a lot of the occurrences of rock have a black surface color. This is not their natural color, rather this is staining due to mining practices--acid rain-corroded rocks that in turn trap metal particulates, giving the rocks a dark surface. There were many instances where we found an outcrop that looked to have a dark matrix with lighter-colored clasts, only to realize that the "clasts" were in fact where sections of the dark surface broke off, revealing the fresh, unstained rock interior below. While many of the outcrops we stopped at fit this description, there were too outcrops that bore promise: one where the different clast lithologies were easily visible and stood out in comparison with the fairly unstained matrix, and another stop where several clasts looked to have a prominent relief compared with the rest of the unit, possibly indicating differential erosion.

After consulting with Oz, we become more confident that we had made observations of Sudbury Breccia for at least a couple of our stops. After mapping a promising outcrop on that Thursday morning, the following day had us returning to the general area of the first outcrop with likely Sudbury Breccia. At the onset of this mapping session, the inimitable Tara scouted out a few more promising outcrops, and by mid-day, we were swimming in Sudbury Breccia!

Tired but eager to relay our findings to our peers, we informally presented on our fieldwork that evening, and less than 24 hours later, we were back home-- myself, Daliah, and Andrew in London, and Tara in Texas. My first time out in the field in quite some time proved to be an impactful endeavor, and I was glad to get some more field experience under my belt in advance of the fieldwork I'll be conducting for my PhD research, looking at the surface roughness of rocks in Iceland and possibly Devon Island. To end, here are some more pictures from the field.